Acaba Su Piresi mi?

Bu konuda bir veri veya haber olmadığını söylüyorum; varsa da öğrenmek isterim zira ben de senelerdir su piresi kullanan hobicilerdenim, kendimi bile bile tehlikeye atmak istemem.

Beğenenler: [T]187204,Bisnev99[/T]

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

Külköylüoğlu, AA muhabirine yaptığı açıklamada, Ostracodaların dünyada bilinen 60 bin türü olduğunu ifade etti.

Okan Külköylüoğlu, şu bilgileri verdi:

''Biz su içinde yaşayan mikroskobik, boyları 0,3 ile 1 milimetre arasında değişen omurgasız hayvanlar üzerinde çalışıyoruz. Bu canlılara Ostracoda diyoruz. Bu canlılar su içinde besin zincirinde önemli bir parçadır. Özellikle yavru balıklar ilk zamanlarda yüzde 70'e yakın bu canlılarla beslenirler. Ostracoda türleri içerisinde sadece tatlı suda yaşayanlar üzerinde çalışıyoruz. Bu canlı midye gibi ancak gözü, ayakları ve yüzebilme özelliği var. Bu canlılar öldükleri zaman kabukları toprağa çöküyor. Kabuk kalsiyum karbonat yapılı olduğu için 400-500 yıl kadar orada kalabiliyor. Bu sularda yaşayan canlıların yaşadıkları ortamın özelliklerini yine bu canlılardan anlayabiliyoruz. Bir gölet kuruduğunda toprağın içerisinde kalan Ostracoda fosillerini bulabiliyoruz. Bu fosillerle o alanda daha önceden bulunan suyun ve çevrenin özelliklerini görebiliyoruz. Dolayısıyla o göletin ne zaman ve nasıl oluştuğunu öğrenebiliyoruz. Bulunan fosillerden o bölgede ne kadar oksijen miktarı olduğunu dahi görebiliriz. Ostracoda'ların ortam ayırıcı bir özelliği var'' diye konuştu.

Bolu'da yaptıkları 10 yıllık çalışmalar sonucunda, yaklaşık 40-50 Ostracoda türü olduğunu belirlediklerini, bölgeyi tamamen inceleme imkanı bulamadıklarını söyleyen Külköylüoğlu, araştırmalar sırasında dünyada sadece dişilerinin olduğu bilinen bir türün erkeğini, bunun dışında Türkiye'de hiç bilinmeyen birkaç tane farklı Ostracoda bulduklarını da ifade etti.

-''ÇUBUK GÖLÜ İNCELEMEYE ALINDI''-

TUBİTAK destekli olarak Çubuk Gölü'nde çalışma başlattıklarını söyleyen Külköylüoğlu, şunları kaydetti:

''Çubuk Gölü'nde 30 ay sürecek bir çalışma yapacağız. Önçalışmalarımız tamamlandı. Yaklaşık 30 önçalışma gerçekleştirdik. Burada sadece Ostracodaları değil, diğer canlı türlerini de inceleyeceğiz. Bu proje TÜBİTAK tarafından takdirle karşılanan bir proje oldu. Bu projede dünyada daha önce denenmemiş dört farklı araştırma şekli bulunuyor. Öncelikle tarlalara atılan böcek öldürücülerin ve kanalizasyon sisteminin göle etkisini inceleyeceğiz, radyoaktiviteye bakacağız. Özellikle radyoaktivite çok önemli. Türkiye'de daha önce yapılmayan bir çalışma olacak. Ostracoda fosillerinin incelenmesinin ardından da gölün ne zaman oluştuğu, nasıl oluştuğu ve ne kadar ömrünün kaldığını belirleyebileceğiz. Bu sayede gölü nasıl koruyabileceğimizi öğrenmiş olacağız.''

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

Arkadaşlar ben cidden çok korkuyorum çünkü su piresi akvaryumumdan sifonlama yaparak(Bilinen su çekme yöntemi) pet şişeye doldurdum.Yani sudan biraz ağzıma kaçtı.O 1 metreye kadar ulaşabilen ve vücutta 1 sene kalıp sonra herhangi bir tarafımızdan baş vererek çıkan parazit bana geçti diye korkuyorum cidden.Anıl bey uzun zamandır üretiyormuş.Anıl bey acaba kaç seneden beri üretiyorsunuz ve sizin de ağzınıza su falan kaçtığı olmuş mudur?Eğer gerçekten tehlikeli bir durum varsa bir iki ay sonra check up yaptıracağım 1 sene yediğimi içtiğimi onunla paylaşmak istemiyorum.

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

HAY akşam akşam güleceğim yoktu yaaa kim den çıkardınız bunu ben uzun zamandır pire üretip satıyorum kızım olum eşim zaman zaman herkes tanklara müdehale ediyor kimse ölmedi

ayrıca su piresinin kendisi parazit taşıyıcısı değildir :)))))))))))))))

İşin en kötü tarafı hakında yeterince bilginiz olmadan insanları yanlış yönlendiriyorsun şimdi senin yazdıklarını okuyup insan inansa yazık değilmi bir işi araşdırmadan bir daha sakın tavsiyede bulunmayın çünkü yanlış bilgi verdiğiniz kişinin hakına girmiş olursunuz dikatli olun .

Bu arada evet canlını türü ostracod yavru balıklar afiyet ile yer

hiç bir zararı da yokdur onalrı da üretip satıyorum çünkü nerdeyse artemia kadar boyu pirenin 3/1 kadar olup ufak balıkların rahatlıkla yiye bileceği bir türdür .

[/QUOTE]

Kendisi birer parazit taşıyıcısıdır. Bizzat derste konu olarak işledik. Ben iki üniverste okuyorum gerek çevre sağlık bölümünde hidroloji dersi olsun gerek loborant ve veteriner sağlık bölümümde olsun bu dersleri alıyorum. Ben bilgi vermek için bilgi vermek istemem bu yüzden de kimsenin hakkına girmem peki siz benim hakkıma girmediniz mi şimdi?

Size sınırsız kaynak bulabilirim.

Bilimsel bir makale:

http://duffylab.biology.gatech.edu/Halletal2010BioScience.pdf

Türkçe olsun derseniz:

http://www.ilaclama.name/pire_ilaclama.asp

Haber niteliği olsun derseniz:

http://www.haberciniz.biz/foto-galeri-dunyanin-en-korkunc-parazitleri--1016-p3.htm

Gine paraziti başlı başına bulaştırıcılarıdandır. Google arama:

http://www.google.com.tr/search?sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8&q=Gine+paraziti

Ben uyarımı yaptım bilmediğiniz yerden su piresi almayın, yine alıyorsanız taktir sizin.

Abi verdiğn makalelerde hepsinde karada yaşayan pirelerind en bahsediyo

verdiğn makalerler haber kaynaklı doğruluğu beli değil sadce 2 makele var onlarda pireleirn yaşam döngüsünden bahsediyor hasatlıklardan değil bana sadece üniversite kaynaklı araşdırma göster

şow yapma

Daphnia dentifera besliyoruz biz konuyu saptırma

Not: Almanca ve ingilizce biliyom dikat et :))Guinea-parasite (Gine parasiti) bu

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

En ufak aramamda bile düzinelerce yazı çıkıyor.

http://www.themoneytimes.com/node/112580

Burada da ve bir çok kaynakta da su piresinden bulaştığı yazıyor

http://www.dhpe.org/infect/guinea.html

Siz yani daphnia hiç bir hastalık taşımadığını mı iddia ediyorsunuz?

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

o yüzden evrim teoriçilerin yıldızı dır daphia ama şu var beslediğiniz suyun içinde zararlı bakteriler ve parazitler varsa o başka ben sadece ama sadece dapiha yetişdiriyorum şuana kadar çok ama çok makale okudum ama daphia nin kesinlikle ara konağı olmadığını biliyorum fakat ona benzeyen başka çanlılarla karışdırılmasın bakın

Copepods, Cyclops bun dan uzak durun derim bunun bünyesinde barına biliyo.

Water Fleas, Daphnia, su piresi budan değil ama bu ara konağı değil

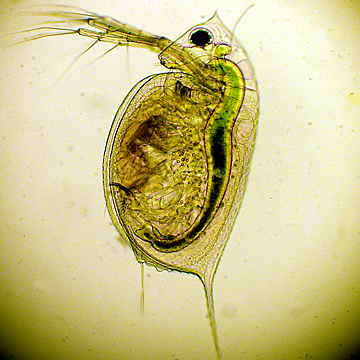

Daphnia, suda yaşayan, pire gibi zıplayan su omurgasızlarını içeren cins. Akvaryum balıklarının beslenmesinde kullanılır. Eklem bacaklılar şubesine ait bu hayvanların boyutları 0.2 ile 5 mm arasında değişir. Uygun sıcaklıktaki (15-22 derece) su birikintilerinde, nehir kenarlarında, tatlı su ve göllerde, bataklıklarda yaşar. Bahar aylarında partenogenez olayı ile ürerler ve bu üreme, yaz sonuna kadar devam eder.

Akvaryumcular tarafından canlı yem olarak kullanılırlar. Tatlı su balıklarının dışında çeşitli böcekler tarafından tüketilirler. Laboratuvarlarda yapılan deneylerde deney hayvanı olarak kullanılmaktadır. Dynamic energy budget teorisinin bulunmasında da bu canlılar rol oynamıştır. Ayrıca akvaryum ve su tanklarının yosunlardan arındırılması işleminde de kullanılırlar.

Üretimi son derece basit ve masrafsızdır. Günde yüz kat çoğalabilme özellikleri vardır. Bu da canlı yem üreticileri için bulunamaz bir fırsattır. Çoğu evcil balık yetiştirme merkezlerinde bu canlıdan bolca faydalanılır.

Zarlı organelleri bulunur. Oksijensiz solunum yapar. Heteretrof beslenme yapar. Gruplar halinde yaşarlar (Sürü psikolojisi). Diğer canlılara karşı Son derece agresif bir tutum sergilerler. Alman bilim adamı Hanz Stumpphan bu canlının bir çeşit zooplanktontan evrimleştiğini bir tezinde dile getirmiştir.

Bakın tekrar söylüyorum gine hastalığı daphia dan bulaşmaz bu familya çok geniş .

Bu Arada ben gicinimi pire satarak sağlamıyorum onu da belirtim sadece hobi amaclı satıyorum .

[QUOTE=Batuaydin] Size 7 dilde Harward'dan 50 makale bile bulsam ticaret kapınız olduğu için reddedeceksiniz.

En ufak aramamda bile düzinelerce yazı çıkıyor.

http://www.themoneytimes.com/node/112580

Burada da ve bir çok kaynakta da su piresinden bulaştığı yazıyor

http://www.dhpe.org/infect/guinea.html

Siz yani daphnia hiç bir hastalık taşımadığını mı iddia ediyorsunuz? [/QUOTE]

Ya bak halen gine hastalığından bahsediyo daphina dan değil sizden rica ediyorum telefonumu çaldırın ben sizi aricam makaleleri beraber okicaz olurmu çok ama çok rica ediyorum ya yoruldum ya alla alla

Gine hastalığının dphina ileee hiç bir alakası yok ya yılardır akvaristler su piresi üretiyo dip cekimi yapiyo hangimizin bir yerinde solucan cıkdı yada gelin evime 1-2 haftaya kadar microscop gelecek beraber inçeliyelğim verdiğiniz bütün makaleler parazitler için ara konaklığı yapan canlılar ki bunun çoğuda karada yaşayan pireler le ilgili karada yaşayan pire ile ne alakamız var yapmayın lütfen

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

Taşıyıcı canlı cyclops, daphnia değil.

Daphnia'nın taşıması imkânsız mıdır ? Bilimde asla asla dememek lâzım, o yüzden tedbirli olmakta fayda var. Şu anda su piresinin (daphnia) taşıyıcı olduğuna dair bir bilgi yok; bir makale, bir deney olursa oturur tartışılır. O zamana dek birbirimizi boş yere kırmaya ya da panik yaymaya gerek yok diye düşünüyorum.

Beğenenler: [T]187204,Bisnev99[/T]

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

http://www.akvaryum.com/Forum/bilimsel_acidan_su_pire_k472922.asp

Water flea'nın diğer adı su piresidir.

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

Su piresi zaten water flea, nam-ı diğer daphnia'dır. Cyclops başka bir canlıdır ve sizin verdiğiniz haberde de, Aytekin beyin yukarda verdiği çizimde de su piresi olarak cyclops gösterilmiş. Yani hastalığı taşıyan daphnia değil cyclops.

Su piresi zaten water flea, nam-ı diğer daphnia'dır. Cyclops başka bir canlıdır ve sizin verdiğiniz haberde de, Aytekin beyin yukarda verdiği çizimde de su piresi olarak cyclops gösterilmiş. Yani hastalığı taşıyan daphnia değil cyclops.

Beğenenler: [T]187204,Bisnev99[/T]

+1: [T]187204,Bisnev99[/T]

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

http://www.akvaryum.com/Forum/bilimsel_acidan_su_pire_k472922.asp

Water flea'nın diğer adı su piresidir.[/QUOTE]

Bu makele yi baya uzun zaman önce görmüşdüm

american katolik kilisesine balğılı olan bir grup üniversite hemen konuya el koydu çünkü makale şuan dünyada darvincilerin başını cekdiği bir araşdırma grubu olan : http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v450/n7171/full/nature06291.html

tarafından yayınlanmışdır

Bu makaleyi gören Katolik killisesine bağlı olan ünüversiteler hemen karşı tezi yayınladılar zaten katılımda bulunan ünvesiteler .

- Laboratory for Animal Biodiversity and Systematics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Charles de Bériotstraat 32, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

- Interdisciplinary Research Center (IRC), Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Campus Kortrijk, Etienne Sabbelaan 53, 8500 Kortrijk, Belgium

- Universität Basel, Zoologisches Institut, Evolutionsbiologie, Vesalgasse 1, 4053 Basel, Switzerland

- Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), UR1282, Infectiologie Animale et Santé Publique, Nouzilly, F-37380, France

Orjinal makale de bu hadi bakalım hangisi gercek sen karar ver abi

Ameiotic recombination in asexual lineages of Daphnia

- Angela R. Omilian * , ,

- Melania E. A. Cristescu *,

- Jeffry L. Dudycha , and

- Michael Lynch *

+ Author Affiliations

- *Department of Biology, Indiana University, 1001 East Third Street, Bloomington, IN 47405; and

- Department of Biology, William Paterson University, 300 Pompton Road, Wayne, NJ 07470

-

Edited by Barbara A. Schaal, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, and approved October 9, 2006 (received for review July 28, 2006)

Abstract

Despite the enormous theoretical attention given to the evolutionary consequences of sexual reproduction, the validity of the key assumptions on which the theory depends rarely has been evaluated. It is often argued that a reduced ability to purge deleterious mutations condemns asexual lineages to an early extinction. However, most well characterized asexual lineages fail to exhibit the high levels of neutral allelic divergence expected in the absence of recombination. With purely descriptive data, it is difficult to evaluate whether this pattern is a consequence of the rapid demise of asexual lineages, an unusual degree of mutational stability, or recombination. Here, we show in mutation-accumulation lines of asexual Daphnia that the rate of loss of nucleotide heterozygosity by ameiotic recombination is substantially greater than the rate of introduction of new variation by mutation. This suggests that the evolutionary potential of asexual diploid species is not only a matter of mutation accumulation and reduced efficiency of selection, but it underscores the limited utility of using neutral allelic divergence as an indicator of ancient asexuality.

It has long been assumed that the absence of meiosis reduces rates of homologous recombination to evolutionarily unimportant levels in asexual eukaryotes. The resultant reduction in the efficiency of natural selection is expected to magnify the rate of deleterious mutation accumulation and reduce the rate of fixation of adaptive mutations, condemning asexual species to an early extinction (14). Yet, despite this bleak theoretical forecast, some lineages, including the bdelloid rotifers (5), oribatid mites (6), and darwinulid ostracods (7, 8), dispensed with sexual reproduction long ago, and the majority of animal phyla have some obligately asexual species (9).

A substantial body of theory has been developed to account for the evolutionary persistence of asexual species (or lack thereof), but only a few large-scale empirical surveys have been undertaken to characterize the molecular genetic consequences of asexual reproduction (e.g., refs. 10 and 11). It has been suggested that the absence of meiosis in asexual lineages causes the two alleles at any given locus to become progressively more divergent given that within-individual recombination (gene conversion and/or crossing over) and chromosomal deletions occur at negligible levels (5, 12, 13). However, with the exception of the bdelloid rotifers, most closely studied asexual lineages fail to exhibit high levels of neutral allelic divergence (e.g., refs. 5 and 1416). These observations call attention to other processes that might erode allelic divergence in real biological systems, such as recombination, unusually effective DNA repair, automixis, or clandestine sexual reproduction (e.g., refs. 1216). Direct experimental observations on the genomic stability of asexual lineages are necessary to shed light on this issue.

Although mitotic recombination has been studied in many organisms for decades (e.g., refs. 1720), recombination in the germ line of asexual species has rarely been directly evaluated. Here, we define ameiotic recombination as either the reciprocal (crossover) or nonreciprocal (gene conversion) exchange of genetic information in apomictic germ-line cells, and we investigate this process in 96 mutation-accumulation (MA) lines of two microcrustaceans: Daphnia pulex and Daphnia obtusa. The MA individuals derived from D. pulex were determined to be obligately asexual, whereas D. obtusa is a cyclical parthenogen. The MA lines were established from three separate isolates (denoted D. pulex: LIN, OL3; D. obtusa: TRE), with replicate sublines being propagated asexually by single-progeny descent in a benign environment for an average of 83 generations. Genetic changes in the MA lines were investigated by genotyping 126 microsatellite loci and sequencing 16 nuclear protein-coding loci. Spontaneous loss of heterozygosity resulting from ameiotic recombination was discovered at many loci.

Results

Of an initial microsatellite survey of 2,917 informative assays, we detected 34 instances of a locus becoming homozygous, which we refer to as loss of heterozygosity (LOH) incidents (Table 1 and Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Eighteen LOH incidents occurred in the LIN lines, 16 in the TRE lines, and none in the OL3 lines. The allele that was shorter in length was lost in 67% of the LOH incidents for LIN and in 88% of the incidents for TRE. On average, 45% of informative microsatellite loci in LIN and TRE experienced LOH in at least one line. The number of LOH incidents per individual line varied from zero to eight, although if loci that experience LOH are linked physically, these events are not necessarily independent of each other.

Summary of loss of heterozygosity information for each MA lineage

Of the 16 protein-coding loci, 88% for LIN, 69% for OL3, and 31% for TRE were informative in that at least one heterozygous site was observed in the assayed fragment. We detected 13 LOH incidents for these loci: seven for LIN, six for TRE, and zero for OL3 (Table 1). With only one exception, all LOH tracts encompassed the entire length (5001,000 bp) of the sequenced fragment (Table 2).

LOH incidents from the LIN lines were mapped in linkage groups I, II, and III of the Daphnia pulex genetic map (ref. 21; Fig. 1). If LOH is due to crossing over, it is expected that homozygosity would exist for all markers distal to a crossover event. Indeed, this phenomenon is observed in linkage group III, where one mutation-accumulation line has lost heterozygosity for 15 adjacent markers, spanning a distance of 115 centimorgans, and appearing to extend for an entire arm of a chromosome. All other LOH tracts observed in our data set were restricted to the most terminal marker of the linkage group or less than four centimorgans in length, so for these events, we cannot differentiate between gene conversion and a double crossover. Two markers underwent LOH in at least eight individuals. For linkage group III, two individuals had experienced three similar (but not the same) LOH events.

Map locations of LOH in linkage groups I, II, and III for the LIN mutation-accumulation lines. The ancestral diploid state for each linkage group is shown on the left, with heterozygous (informative) loci denoted by black type and uninformative loci in gray type. Numbers to the left denote map distances (centimorgans), and numbers to the right indicate marker names. Loci revealing LOH are denoted with arrows, and numbers of individuals experiencing a particular LOH profile are given below each profile. Arrows pointing right denote loss of the shorter allele, and those pointing left denote loss of the longer allele.

There are several ways to quantify the rate of LOH with these data. For the protein-coding loci, the rate of incidents per locus is almost identical to the rate of LOH on a per-nucleotide basis because almost all exchanges encompass the entire locus. These rates vary considerably among the sets of experimental lines and have an overall average (including the OL3 lines that did not exhibit LOH) of 0.00016 (0.00009) per locus and 0.00021 (0.00013) per nucleotide per generation (Table 1). Similar estimates were obtained for the rate of LOH in the genomewide survey of microsatellite loci, with an average of 0.00012 (0.00006) over all lines (Table 1). A somewhat higher microsatellite-based estimate is obtained from the survey of mapped loci in the LIN lines, 0.00032 (0.00005), and from these data, the minimum rate of exchange events per chromosome per generation is estimated to be 0.00467 (0.00069).

Discussion

Could our observed instances of LOH be artifacts of processes other than ameiotic recombination? PCR artifacts, such as the preferential amplification of one allele, are unlikely to explain our data. For each putative LOH incident in our protein-coding data set, we performed an additional PCR, and many of these confirmatory PCRs were performed with a different type of Taq polymerase and/or DNA extraction. Resequencing confirmed all LOH incidents included in this analysis. The occurrence of null alleles due to mutations in priming sites is a remote possibility. However, point mutations in the animal nuclear genome have been measured to occur at a frequency of ≈10−8 to 10−7 per site·generation−1 (22), and given an average primer length of 20 bp and the extremely conservative assumption that one mutation within a priming site causes amplification failure, the chance of a null allele at any given locus is not likely to exceed ≈8 × 10−6 per locus·generation−1. Because our observed rate for LOH is ≈10−4, it is unlikely that null alleles explain LOH in Daphnia. Moreover, our mapped data provides spatial evidence against null alleles. Most convincingly, in linkage group III, 15 independently amplified adjacent markers experience LOH; when linked loci show simultaneous transitions to homozygosity, ameiotic recombination is clearly a better explanation.

A general loss of heterozygosity also could arise from mating between male and female members of the same line. This is a very remote possibility for the cyclically parthenogenetic TRE lines because these lines are capable of sexual reproduction. However, the 50% reduction in genome heterozygosity that is expected after a bout of intraclonal mating was not observed in any of our MA lines. Only 3 of 35 TRE lines exhibited LOH at more than a single locus; the genomewide levels of LOH for these three lines were just 7%, 14%, and 36%. The possibility of intraclonal mating is even more improbable for the LIN lines because they are derived from an obligately asexual clone. Assays of 14 heterozygous microsatellite loci in 12 replicate hatchlings obtained from LIN dormant eggs were 100% consistent with the maternal genotype (probability = 2.7 × 10−51 under the assumption of random selfing). Moreover, most LIN individuals experiencing LOH did so for only one locus (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Thus, the possibility of clandestine sexual reproduction in our MA lines can be ruled out.

Nondisjunction or partial chromosome deletion can result in LOH, although it should be emphasized that deletions can be produced as a result of recombination (23), so their presence does not necessarily preclude the occurrence of recombination. In any event, several lines of evidence indicate that deletions are unlikely to explain our data. First, every mapped tract of LOH was linked physically with other markers that retained heterozygosity (Fig. 1), demonstrating the presence of two distinct chromosomes. Second, one mapped LOH event spanned nearly the entire mapped chromosome length, covering a distance of at least 100 centimorgans. Chromosomal deletions of this magnitude are unlikely to be tolerated by most animals because of the exposure of deleterious recessives or haploinsufficiency. Third, our observed instance of partial LOH is evidence against hemizygosity, because the cloning and subsequent sequencing of this locus revealed two distinct alleles. Although we cannot entirely rule out partial chromosomal deletions as a mechanism for LOH at some loci, very small deletions would be expected to yield unexpectedly short PCR products, which we never observed.

Studies of somatic tissues often report that LOH is due to mitotic recombination (e.g., refs. 2427), and studies of mitotic recombination describe features of this process that we observed in our data. First, mitotic recombination has been reported to show hot spots of activity (e.g., 20, 24, 28). Hotspots of ameiotic recombination also may occur in Daphnia, because 21 of the 27 LIN chromosomes with mapped LOH events were associated with just two of the 46 informative markers (Fig. 1). Most LOH incidents were at the most terminal mapped marker for a given chromosome, indicating that LOH may occur more readily at distal chromosome regions in Daphnia. Alternatively, proximal crossovers would cause more loci to become homozygous, thereby increasing the likelihood of exposing lethal recessives, leaving the false impression of a higher recombination rate in distal regions. In either event, one prediction that should be addressed with future studies is that asexuals may be more homozygous at distal chromosome regions than their sexual counterparts, and ancient asexuals may have a greater percentage of homozygous chromosome tips than young asexuals.

Second, previous studies of mitotic recombination report negative interference such that one recombination event increases the chances that another event will occur on the same chromosome (20, 29). In our data set, two individuals had LOH profiles, suggesting that at least four exchange events resulted in two LOH tracts at the tips and one in the interior of linkage group III (Fig. 1). Excluding these two individuals from the analysis yields an estimated rate of exchange events for linkage group III of 0.00417, similar to the overall average noted above, which implies an ≈0.0005 probability of observing four or more events on one chromosome after 83 generations in the LIN lines under the assumption of no interference and an ≈0.0002 probability of observing two of 40 lines with such an extreme condition. Our data tentatively support the hypothesis of negative interference (reinforcement) between recombination events.

Thus, our direct observations are fully consistent with the frequent occurrence of recombination in asexual lineages of Daphnia. In our experimental lines, ameiotic recombination frequently causes LOH rates (λ) >10−4 per site·generation−1. In contrast, for animal species, the rate of base-substitution mutation (μ) is ≈10−8 to 10−7 per site·generation−1 (22). This implies that spontaneous LOH resulting from ameiotic recombination in Daphnia occurs ≈1,000× faster than the rate of production of new nucleotide heterozygosity by mutational input. Although this recombination is internal and does not allow genetic exchange across lineages as in outcrossing sex, our observation of ameiotic recombination shows that one of the bedrock assumptions of evolution-of-sex theory, that asexual lineages acquire variation through mutational input only, is substantially violated in a real biological system.

These results challenge the view that the two alleles at any given locus will indefinitely accumulate independent mutations when sexual reproduction ceases within a diploid lineage, the so-called Meselson effect. In the absence of any cross-talk between alleles, the expected rate of gain of sequence heterozygosity at neutral homozygous sites is 2μ, and with simultaneous occurrence of LOH, the expected equilibrium level of sequence divergence at neutral sites is 2μ/[(8μ/3) + λ], or between 0.0002 and 0.0020 at the rates noted above. Because the average (and SD) standing levels of silent-site heterozygosity in sexually reproducing vertebrates and invertebrates are 0.0041 (0.0030) and 0.0265 (0.0142), respectively (22), and similar values can be expected for newly arisen parthenogens, our results provide a simple explanation for the low levels of allelic divergence frequently encountered in asexual lineages. With ameiotic recombination eliminating heterozygosity so much faster than mutation replenishes it, clonal lineages are generally expected to experience losses of allelic variation over time except when initiated from unusually homozygous individuals, and even in the latter case, the increase is unlikely go beyond what is typically seen in outcrossing species.

There are two potential concerns with the generality of this conclusion. First, one set of lines in our study (OL3) yielded no evidence of ameiotic recombination. Using the average rates for the LIN and TRE lines (Table 1), the probabilities of observing no LOH incidents at protein-coding and microsatellite loci in the OL3 lines by chance are 0.0394 and 0.0009, respectively. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the OL3 lineage has a substantially reduced recombination rate, as drastic rate differences have been reported in other systems (30), an alternative possibility is that the ancestral OL3 genotype harbors a substantial load of recessive deleterious mutations. Exposure of inviability or sterility mutations by LOH events would prevent the propagation of lines that experienced ameiotic recombination, leading to the false impression of reduced recombinational activity. The OL3 lines were notably less hardy than either the LIN or TRE lines: We resorted to backup stocks twice as often in the propagation of OL3 lines (doubling the opportunity for selection), the number of lines surviving to the time of assay was reduced by ≈50%, and the average number of generations was reduced by ≈36% (Table 1). Sexual clones within the D. pulex complex often exhibit substantial inbreeding depression (31), and for this reason, even our estimated rates of recombination in the LIN and TRE lines may be downwardly biased.

A second issue of relevance is the impact of chromosomal location on the sensitivity of a locus to LOH. Although we are unable to formally distinguish between large tracts of gene conversion and crossover events for most chromosomal alterations, some regions appear to be much more vulnerable to ameiotic recombination than others (e.g., the tips of linkage-group III; Fig. 1). With a mutation rate of μ = 10−7, a 100-fold reduction of λ to 10−6 would lead to an expected silent-site heterozygosity of 0.158 under mutation-recombination balance. Because this level of divergence will act as a strong deterrent to homologous recombination (32, 33), regions with low λ can be expected to enter the domain of the Meselson effect, i.e., indefinite neutral allelic divergence. Thus, to a degree that depends on the regional constraints on recombination and the stochastic nature of the process, asexual genomes may progressively develop mosaic patterns of allelic divergence, as may be the case in bdelloid rotifers (5).

Nevertheless, our results are consistent with many other studies that have failed to find high levels of allelic divergence in asexual organisms. Recombination often has been suggested as one of several possible reasons for this observation (1215, 3437). However, previous studies have been unable to convincingly rule out other possible explanations for this phenomenon, such as a more recent transition to asexuality than expected (14), low mutation rate (15, 35), or sexual reproduction (14). Even studies that infer recombination based on phylogenetic or other statistical approaches suffer from the uncertainty that the detected recombination events occurred before the lineage transitioned to asexuality (37). By allowing the direct tracking of chromosomal alterations while also ensuring that sexual reproduction is not occurring, our Daphnia MA lines provide a convincing demonstration of substantial heritable recombination in the absence of meiosis.

Although a substantial body of theory has addressed the evolutionary advantages of sexual vs. asexual reproduction, nearly all such theory assumes that the loss of sexual reproduction is accompanied by the complete loss of recombination. Thus, our observations have three major implications for our understanding of the consequences of transitions to asexuality. First, the occurrence of ameiotic recombination helps explain the dearth of allelic divergence observed in many putatively ancient asexual lineages, underscoring the risks associated with the use of neutral allelic divergence to estimate the age of diploid asexuals and demonstrating that ancient asexuals are likely to be more widespread than previously thought.

Second, ameiotic recombination provides some evolutionary flexibility in asexual lineages. Depending on the location of recombination breakpoints and the manner in which heteroduplex DNA is resolved, asexually produced progeny may inherit alleles that are mosaics of the parental alleles, a substantial contrast to conventional wisdom that acknowledges mutational input as the only source of new variation.

Third, recombination will alter the expected extinction dynamics of an asexual population. Because 25% of the progeny experiencing an ameiotic recombination event will be homozygous for each parental chromosomal region within the tract, some offspring clones (those with a net exposure of deleterious recessive alleles) will be worse off than the parent clone, whereas a subset might experience improved fitness relative to the heterozygous parental state. Whether the latter condition will occur at an appreciable frequency will depend on the net distribution of heterozygous and homozygous fitness effects of mutations within a typical recombination tract. Deleterious mutations with the maximum effect on the viability of clonal populations are those with effects in the neighborhood of 1/N e, where N e is the effective population size, because these mutations are quite vulnerable to fixation by random genetic drift while still having an appreciable effect on fitness (38). Because ameiotic recombination effectively reduces the rate of long-term inheritance of mutations by 50% while at least doubling their effects (depending on the degree of dominance) (39), the degree to which ameiotic recombination influences the viability of asexual lineages will depend critically on the extent to which the distributions of deleterious fitness effects of heterozygous vs. homozygous mutations reside within the vicinity of 1/N e. Because the details of these parameters remain to be determined, it is premature to say whether our results mean that the evolutionary prospects of asexuals are better or worse than previously believed, but the fact that LOH is occurring at a much higher rate than mutation indicates that conventional theoretical models for the evolutionary dynamics of asexual populations should be reevaluated.

Materials and Methods

Daphnia Mutation-Accumulation Line Maintenance.

Single female individuals of Daphnia pulex (designated LIN and OL3) and D. obtusa (TRE) were isolated from three temporary ponds (located in Linwood, ON, Canada; Barry County, MI; and Trelease Woods, IL, respectively). Most Daphnia are cyclical parthenogens, capable of both sexual and apomictic reproduction. However, obligately asexual lineages do exist (4042), and asexual reproduction in several species of Daphnia has been shown to be ameiotic (e.g., refs. 43 and 44). LIN and OL3 were determined to be obligately ameiotic parthenogens, whereas TRE was determined to be a cyclical parthenogen by following established methods in ref. 45.

Daphnia were maintained under standard conditions at 20°C and fed ad libitum with a suspension of vitamin-fortified Scenedesmus obliquus. MA lines were initiated from 48 to 50 single progeny derived from a single stem mother and, subsequently, maintained by following described methods in refs. 46 and 47. Our protocol for propagating lines was as follows: 1012 (LIN), 1214 (OL3), or 810 (TRE) days after the previous transfer, a single randomly chosen daughter was transferred to a new beaker, and two of her sisters were transferred into separate vessels to serve as back-ups, in case the focal individual died without producing female offspring. Backups were used in 1520% of the transfers, usually because the focal individual produced only dormant eggs (OL3 and LIN) or male (TRE) offspring. The use of backups potentially leads to a downward bias in our LOH rate estimates, because LOH that is lethal or substantially retards the production of immediately developing female offspring will be underrepresented.

Microsatellite Loci.

Protocols for microsatellite DNA amplification, genotyping, and primer design are described in Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, and ref. 21. Initially, 59 microsatellite loci were genotyped in 96 individual lines (40 LIN, 21 OL3, and 35 TRE) for a total of 5,664 loci. Forty-three percent of these loci, previously mapped in D. pulex (21), revealed linkage groups in which LOH had occurred. An additional 67 markers were then analyzed on three of the longest linkage groups (I, II, and III) spanning a total genetic distance of 500 centimorgans and an average distance between adjacent markers of ≈7.5 centimorgans. This linkage-group analysis only included the LIN lines (40 individuals), because the OL3 lines did not exhibit LOH, and the TRE lines are derived from an unmapped species.

Microsatellite loci were analyzed with GeneMapper Software v3.0 (Applied Biosystems). Individuals that showed evidence of LOH were reanalyzed with a different dye and an excess of Taq polymerase as a precautionary measure to avoid the differential amplification of one allele (48). Loci that could not be scored unambiguously or manifested a signature of differential amplification of one allele (i.e., pronounced difference in peak height between the two alleles) were excluded from the analysis.

Protein-Coding Loci.

Sixteen protein-coding loci were sequenced for individuals from 96 MA lines (40 LIN, 21 OL3, and 35 TRE) for a total of 1,536 loci. Primers were designed from conserved regions in genes present in both D. pulex and D. magna cDNA libraries (Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Details about DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing of Daphnia nuclear loci are described in ref. 49, and we used similar protocols with the following major exceptions. One unit of Taq polymerase (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) was used for each PCR, and PCR products were purified with solid-phase reversible immobilization (50). LOH incidents were identified as MA-line electropherograms that were devoid of polymorphisms at ancestrally heterozygous nucleotide sites. LOH tracts extended the length of the analyzed fragments except for one locus. This locus was cloned with an Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) TOPO TA kit, a QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used for plasmid purification, and a T7 primer was used to sequence the cloned inserts.

DNA sequence electropherograms were analyzed with CodonCode Aligner software v1.4.3. To rule out PCR and sequencing errors, LOH was confirmed by reamplification with a different Taq polymerase (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and resequencing. Only LOH events supported by data from two independent PCRs were used for our analysis. For the confirmatory PCRs, fresh DNA extractions were often used (50% of the time), and because these extractions were performed at a later date, the extracted individual was advanced in the number of generations of mutation accumulation. For all confirmatory PCRs (including microsatellite loci) that used individuals that were advanced in their number of generations of mutation accumulation, LOH events persisted across generations of asexual reproduction; this indicates that LOH occurs in the germ line and is heritable.

A BLAST search for each protein-coding locus recovered the following highly significant hits: ATP synthase epsilon chain, β-tubulin, calcium binding protein, cell division cycle protein, cleavage stimulation factor, engrailed, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, Rab subfamily of small GTPases, myosin light chain, NADH dehydrogenase, rab11, translation initiation factor, ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, and vitellogenin fused with superoxide dismutase. BLAST did not yield a significant hit for an annotated gene for the following loci: C6C12 and G4G10.

Similar LOH Profiles in Multiple Individuals.

Two individuals had similar LOH profiles that included three discontinuous LOH tracts in linkage group III. The probability of three LOH tracts being shared by two individuals should be prohibitively rare, and at first glance, this appears to be a contamination artifact of either Daphnia cultures or PCR. However, the direction of allele loss varies for one locus between these two individuals: one individual became homozygous for one allele, whereas the other individual became homozygous for the other allele (Fig. 1), and LOH incidents at five other loci differentiate these two individuals. For 66% of the other situations in which similar LOH profiles occurred in multiple individuals, clone contamination could be ruled out on the basis of the direction of allele loss or additional microsatellite mutations or LOH incidents elsewhere in the genome. This suggests that shared LOH profiles are a result of hotspots of recombination rather than contamination.

Calculation of LOH Rates.

The LOH rate was calculated for each MA lineage (LIN, OL3, and TRE) with the equation λ = h / (L·i·T), where λ is the LOH rate (per locus·generation−1), h is the number of observed LOH events, L is the number of MA lines, i is the total number of informative loci, and T is the average number of generations for the MA lines. To obtain a rate per nucleotide site, h is the number of nucleotide sites that became homozygous, and i is the total number of heterozygous sites observed in the data set. The rate of ameiotic recombination per chromosome was estimated based on the linkage group analyses with the same equation. For this calculation, i is the number of informative chromosomes, and h is the number of recombination events. Adjacent loci that experienced LOH were considered to be part of the same recombination event.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Zolan, D. Denver, D. Scofield, T. Crease, D. Taylor, and two anonymous referees for helpful advice; J. Colbourne (Indiana University Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Bloomington, IN) provided the Daphnia cDNA libraries for primer design; and C. Puzio, A. Danielson, V. Cloud, Y. Radivojac, and B. Molter provided technical assistance. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation IGERT fellowship (to A.R.O.), a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council fellowship (to M.E.A.C.), a National Institutes of Health Kirchstein fellowship (to J.L.D.), and National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants (to M.L.).

[QUOTE=an1l]Batu bey, ben onları okudum da siz beni okuyor musunuz merak ediyorum

Su piresi zaten water flea, nam-ı diğer daphnia'dır. Cyclops başka bir canlıdır ve sizin verdiğiniz haberde de, Aytekin beyin yukarda verdiği çizimde de su piresi olarak cyclops gösterilmiş. Yani hastalığı taşıyan daphnia değil cyclops.

[/QUOTE]

Su piresi zaten water flea, nam-ı diğer daphnia'dır. Cyclops başka bir canlıdır ve sizin verdiğiniz haberde de, Aytekin beyin yukarda verdiği çizimde de su piresi olarak cyclops gösterilmiş. Yani hastalığı taşıyan daphnia değil cyclops.

[/QUOTE]Ya bende bunu söyliyorum abi Batuaydin bey telefon acarsa konuyu ona za edicem fakat abi müsait değil .

bundan sonra bir daha böyle bir konya yazarsam ne olim tansyonumu hoplatı adam yaaa....

Bu arada türkiyede okumadığım için türkçe düzgün yazamıyorum özür dilerim yazımdan dolayı .

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir

Hoplamasın tansiyonunuz canım, ne var bunda...Siz yine de yazın. Burası bir forum sonuçta; bilgi-fikir alışverişi yapmayacaksak burda yazmanın anlamı ne ? İnsanlar elbette yanlış olduğunu düşündükleri bir konuda fikir belirtecekler, bunda alınacak gücenecek birşey olmamalı...

Üye imzalarını sadece giriş yapan üyelerimiz görebilir